A growing crisis

In conflict zones like Afghanistan, Yemen, Nigeria, and South Sudan, malnutrition is more than just a humanitarian issue—it’s a race against time. For countless children, it’s the difference between life and death. Doctors Without Borders is working urgently to turn the tide.

Malnutrition isn’t just about going hungry—it’s a life-threatening lack of nutrients. In places where families are already grappling with war, floods, and economic collapse, this crisis is escalating fast.

Latest update

Global overview

-

295 million people across 53 countries faced acute food insecurity in 2024, marking the sixth consecutive year of worsening hunger.

-

1.9 million people are experiencing catastrophic hunger (IPC Phase 5), the highest number recorded since tracking began.

-

38 million children under five were acutely malnourished across 26 countries in 2024.

Child malnutrition

-

150.2 million children under five were stunted (too short for their age) in 2024.

-

42.8 million children under five were wasted (too thin for their height) in 2024.

-

12.2 million children under five suffered from severe wasting in 2024.

-

35.5 million children under five were overweight in 2024.

Child food poverty

-

181 million children under five are living in severe child food poverty, consuming two or fewer food groups daily.

-

South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa account for over two-thirds of children in severe food poverty.

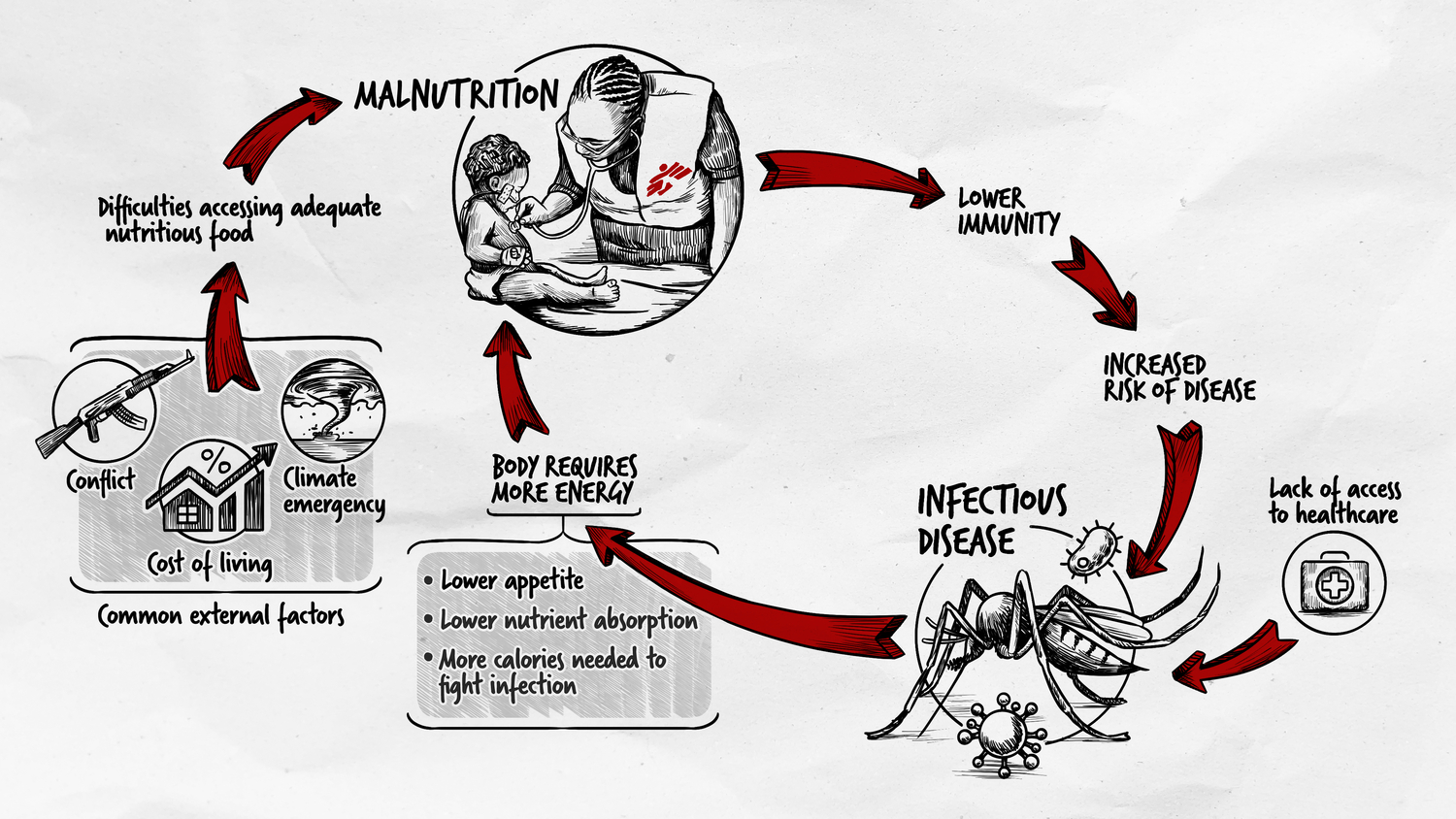

Why is malnutrition rising?

-

Conflict and displacement tear food systems apart.

-

Climate shocks like floods and droughts ruin harvests.

-

Economic instability drives up food prices.

-

The aftermath of COVID-19 continues to strain fragile economies and healthcare systems.

-

In many places, unhealthy food is still cheaper and more accessible than nutritious meals.

There are no shortages of factors contributing to this crisis. A devastating mix of rising food prices, displacement, insecurity, climate-induced crop failures, low immunisation coverage, and a lack of drinkable water and sanitation leave more children susceptible to developing malnutrition. Sustainable strategies to mitigate these factors must continue to be developed – including by MSF. But having worked on this issue for years, I know that aid funding for food alone will not solve the problem. Without it, Nigerian children will continue to die.Dr. Simba Tirima, Nigeria Country Rep.

- Yemen

-

Yemen remains one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, with millions still displaced, and nearly half the population facing food insecurity. Limited access to healthcare, clean water, and food is placing children and mothers at severe risk.

-

The healthcare system is on the brink of collapse, with 46% of facilities either partially functioning or completely non-operational. Aid cuts—including the US decision to terminate support in April 2025—have impacted over 520 health facilities and at least 20 organisations.

-

Doctors Without Borders has treated over 35,000 malnourished children under five in Amran, Saada, Hajjah, Taiz, and Al Hudaydah governorates from 2022 to 2024.

-

Abs Hospital ITFC reached a 200% bed occupancy rate during the 2024 peak in September; Al Salam Hospital in Khamer saw a 254% rate in October.

-

Two-thirds of pregnant and breastfeeding women and girls admitted to MSF facilities are malnourished.

-

The termination of aid is projected to halt nutritional care for 100,000 children and end food assistance for 2.4 million people.

-

Outbreaks of preventable diseases such as measles and diphtheria are resurging due to poor living conditions and low vaccination coverage.

-

Doctors Without Borders is under increasing pressure to compensate for the withdrawal of international actors. We call on donors to urgently scale up support and for authorities to improve healthcare access and implement strong vaccination campaigns.

-

Sanctions and the FTO designation of Ansar Allah are exacerbating hardship, disrupting the import of food, medicine, and essential goods.

-

Doctors Without Borders also denounces recent attacks on Yemen’s civilian infrastructure, including airstrikes on hospitals, ports, and power stations, which have critically undermined access to aid and medical care.

-

- Nigeria

-

Over 328,000 children treated for malnutrition in 2024—a 24% increase from 2023, with most cases concentrated in the northern states.

-

Doctors Without Borders supports 10 inpatient therapeutic feeding centres and 36 ambulatory centres across the country, providing vital care to those most in need.

-

A surge in malnutrition cases began as early as March, months before the typical July peak season.

-

In Kebbi, admissions rose by more than 40% in April 2025 compared to the previous year; in Kano, primary ITFCs are at full capacity, with more centres expected to be overwhelmed.

-

- Madagascar

-

In southeast Madagascar, particularly in Ikongo district, Doctors Without Borders is responding to rising malnutrition driven by food shortages and recent climate shocks.

-

As of January 2023, 2,072 children under five were being treated for severe acute malnutrition across five health centres—nearly half enrolled in Doctors Without Borders programmes.

-

The region faces repeated climate shocks, including cyclones Batsirai and Emnati in 2022, which destroyed over half of the local food crops and devastated incomes for farming families.

-

Over 25% of people in Vatovavy-Fitovinany and Atsimo-Atsinanana are living with acute food insecurity.

-

Doctors Without Borders supports 24 health facilities in hard-to-reach areas and is scaling up efforts to meet rising needs amid a limited humanitarian presence.

-

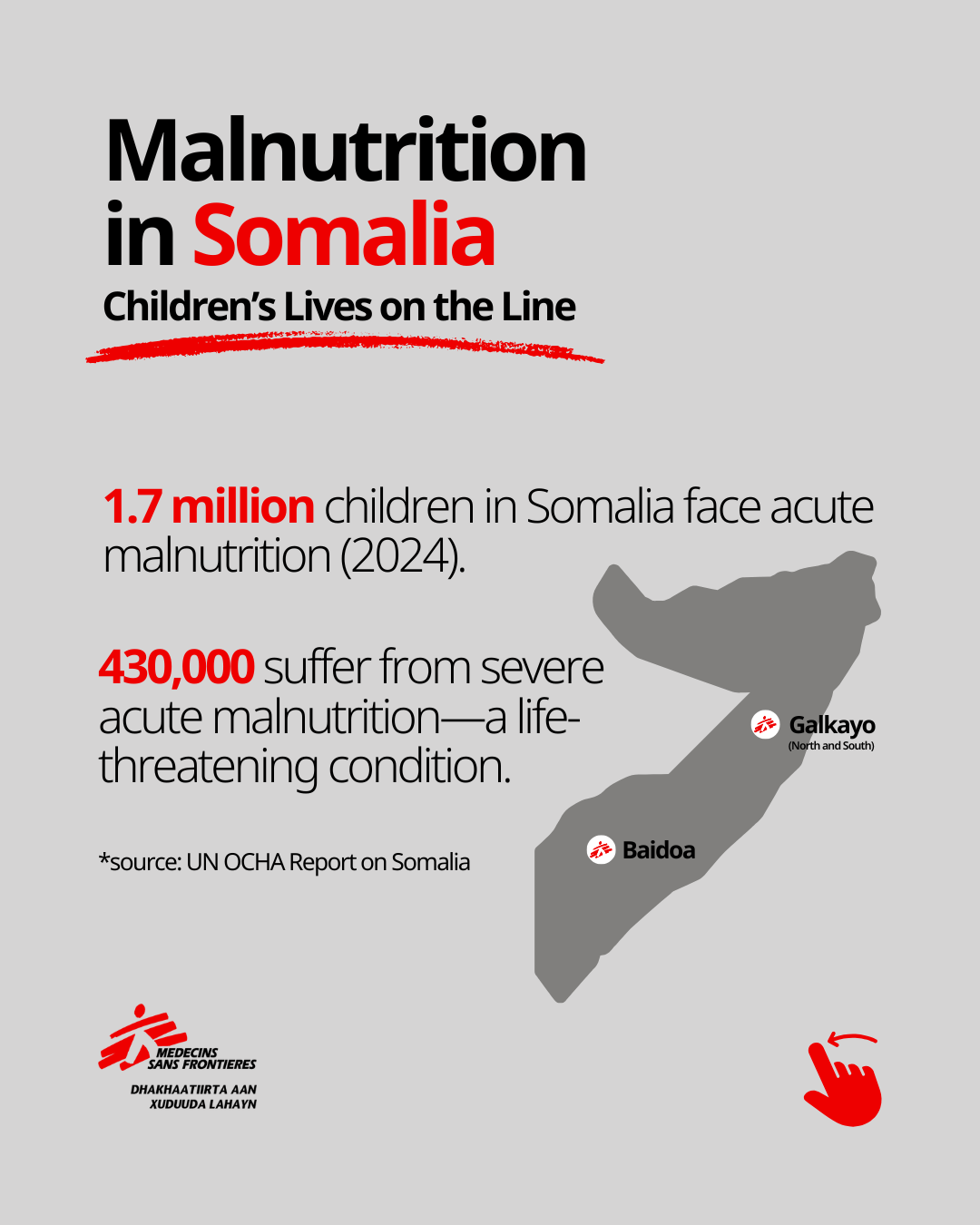

- Somalia

-

Doctors Without Borders operates 20 mobile nutrition clinics and 32 monitoring sites in Baidoa, one of the areas hardest hit by the current drought.

-

Over 206,000 children were screened for malnutrition in 2022, with thousands requiring emergency nutritional care.

-

Between January and August 2022, over 12,000 children were treated for acute malnutrition, with weekly admissions averaging 500.

-

The situation remains critical, with multi-seasonal drought, displacement, and limited access to healthcare severely undermining children’s survival.

-

- Ethiopia

-

Doctors Without Borders is witnessing a severe nutrition crisis in Afar, where malnutrition among children under five has surged following conflict, drought, and a collapse in local healthcare services.

-

At Dupti Hospital, the only functional referral facility in the region, admissions of severely malnourished children have increased by three to four times compared to previous years.

-

Many of these children arrive in critical condition, with mortality rates exceeding 20% in some weeks. Two-thirds of admitted patients are from displaced families who have had no prior access to healthcare.

-

Alarmingly, over 80% of malnourished children admitted have never received earlier treatment and often die within 48 hours of admission.

-

In response, Doctors Without Border has expanded its support to Dupti Hospital, including opening 14 additional beds, strengthening emergency services, and launching plans for new outpatient feeding programmes in hard-hit areas.

-

Damaged or under-resourced health structures remain a key barrier, with only 20% of health facilities in Afar still functional.

-

Clean water access is also a challenge. In one incident, 41 children were admitted in two days with severe stomach infections caused by drinking from muddy puddles.

-

- Kenya

-

Marsabit County has been severely impacted by consecutive failed rainy seasons, leading to high levels of food insecurity and malnutrition, particularly in Illeret and North Horr sub-counties.

-

In February 2022, a mass screening by UNICEF in Marsabit revealed a 23% global acute malnutrition rate, far above emergency thresholds.

-

Between February and March 2022, 11 children in MSF’s malnutrition programme died due to complications from severe acute malnutrition.

-

Outreach clinics have been infrequent due to logistical and human resource challenges—sometimes held only once or twice a month—resulting in poor follow-up and setbacks in treatment progress.

-

Doctors Without Borders, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, is strengthening the inpatient department at Illeret Health Centre to operate as a 10-bed therapeutic feeding centre, while enhancing referral systems and screening efforts to catch cases earlier.

-

Mothers of malnourished children in the facility also receive daily meals to improve lactation and maternal nutrition.

-

- South Sudan

-

Over seven million people in South Sudan are projected to face acute food insecurity between now and July 2025.

-

In Leer, Unity State, Doctors Without Borders is witnessing a dangerous intersection of malnutrition and chronic illness. Patients with TB/HIV are particularly affected, as the side effects of medication become intolerable without food.

-

Some patients reduce or discontinue treatment to avoid severe pain, risking drug resistance and death.

-

Doctors Without Borders has a cohort of over 600 TB/HIV patients in Leer alone. In recent months, new monthly patient intake has doubled from 8 to 16.

-

The defaulter rate is rising as patients cannot adhere to treatment regimens due to hunger. Malnutrition is also compromising immunity, making people more susceptible to illness.

-

Since April 2023, over 60,000 returnees and refugees have arrived from Sudan, further straining food and healthcare systems.

-

Food assistance remains insufficient and non-prioritised, with no mechanisms to specifically support vulnerable groups like TB/HIV patients.

-

- Afghanistan

-

Doctors Without Borders teams operate in Kandahar, Helmand, Herat, Kabul, and Khost, responding to widespread malnutrition among children under five and lactating mothers.

-

In 2023, Doctors Without Borders-supported facilities admitted over 10,400 children under five to inpatient malnutrition programmes in Herat, Lashkar Gah, and Kandahar. From January to April 2024 alone, 2,416 patients were admitted—a 5% increase from the previous year.

-

More than 6,900 children were enrolled in ambulatory therapeutic feeding centres (ATFCs) in 2023.

-

Many cases stem from poverty-driven food insecurity and inadequate breastfeeding, with babies often falling ill after switching to infant formula.

-

Doctors Without Borders facilities are seeing large numbers of young infants, many under one year old, pointing to issues with breastfeeding and a lack of accessible early nutrition support.

-

In some inpatient facilities, two children share a single bed with their mothers due to overcrowding.

-

Patients travel hours from rural provinces such as Badghis to reach care, underscoring the gap in accessible local health services.

-

Doctors Without Borders is responding with both inpatient and outpatient care, as well as health promotion activities aimed at improving breastfeeding practices and complementary feeding.

-

What is Doctors Without Borders doing to address malnutrition?

Doctors Without Borders has been responding to the malnutrition issue in several countries including Afghanistan, Yemen, Nigeria, South Sudan and Madagascar.

In many of our projects, we also respond to individual cases of malnutrition.

Quick facts about malnutrition

Doctors Without Borders screens a community for potential malnutrition by conducting nutritional assessments, and during almost all of our outpatient and inpatient services which are not dedicated specifically to nutrition and during other interventions. Our teams assess children by comparing their weight-for-height ratio to international WHO standards, and/or by measuring a child’s mid-upper-arm circumference (MUAC) using colour-coded paper bracelets. MUAC measurements are also simple enough to be used at a village level by community health workers.

The widespread use of ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), that can be stored long-term without refrigeration and contains a specific balance of nutrients, allows us to more effectively fight against malnutrition. RUTF can be either a paste, much like peanut butter, or in a biscuit form. The majority of children can be treated at home by their family, with follow-up appointments at a clinic. This strategy can result in cure rates of over 90 per cent, and can reduce referral to inpatient care.

In some regions, our teams run malnutrition prevention projects to stop children from falling ill, especially after a yearly “hunger gap”. Doctors Without Borders starts working and sets up outpatient clinics months before malnutrition cases peak at the start of the rainy season. In areas where malnutrition is likely to become severe, our teams take a preventative approach by distributing a nutritious supplement to at-risk children across Africa and Asia and making sure other disease prevention initiatives, like vaccinations and malaria chemoprophylaxis, are implemented.