Extreme heat

The planet is getting hotter — and the health impacts are impossible to ignore. Why is this happening, who’s most at risk, and what can we do to protect ourselves?

Surviving the heat: A public health emergency

In recent weeks, parts of Southeast Asia have recorded temperatures above 40°C — with Myanmar, Thailand, the Philippines, and Vietnam facing prolonged, unusually intense heat. While not officially declared a heatwave, several Indonesian cities are also experiencing sustained temperature spikes.

Extreme heat isn’t just uncomfortable — it’s deadly. It causes nearly 500,000 deaths every year, rivaling malaria in its toll.

The communities we serve are the hardest hit — and the least responsible. Our teams help those affected. Support our mission.

What is extreme heat?

Extreme heat refers to abnormally high temperatures lasting for several days, often worsened by humidity, air pollution, and limited access to cooling. In cities, the “urban heat island” effect traps more heat, making conditions worse.

Not all heat is the same:

- Dry heat: Helps sweat evaporate, offering some cooling.

- Humid heat: Sweat doesn’t evaporate easily, reducing the body’s ability to cool down.

Tools like Wet Bulb Globe Temperature are used to assess risk, factoring in temperature, humidity, sun exposure, and wind. Wet bulb temperature measures how hot it feels when both heat and humidity are high. It’s the lowest temperature the body can cool to through sweating and evaporation.

a8a7.png?itok=OipvSYfC)

Prolonged periods of extreme heat — at least three consecutive days of temperatures significantly above the average for a region — is known as a heat wave. These events are becoming more frequent and severe due to climate change, often intensified by humidity, air pollution, and the urban heat island effect.

Heat waves place enormous stress on the human body, especially when high humidity prevents sweat from evaporating, making it harder to cool down. This can lead to a range of heat-related illnesses:

A common early sign of heat stress, heat rash--also known as prickly heat--appears as red, itchy skin. It’s caused by blocked sweat glands and usually occurs in areas where sweat gets trapped.

These are painful muscle spasms triggered by loss of salt and fluids through heavy sweating, often affecting people working or exercising in the heat.

This occurs when the body loses large amounts of water and salt, leading to symptoms such as heavy sweating, dizziness, fatigue, nausea, irritability, headache, and weakness. If not treated quickly — by cooling down and rehydrating — it can progress to heat stroke.

This is the most severe and life-threatening form of heat illness. It happens when the body can no longer regulate its core temperature and sweating stops altogether. Warning signs include confusion, loss of consciousness, seizures, and a body temperature above 40°C. Heat stroke is a medical emergency and requires immediate treatment.

“Heat stroke is a medical emergency. It can be deadly.”

Subscribe for updates today and get our free Heat Safety Guide.

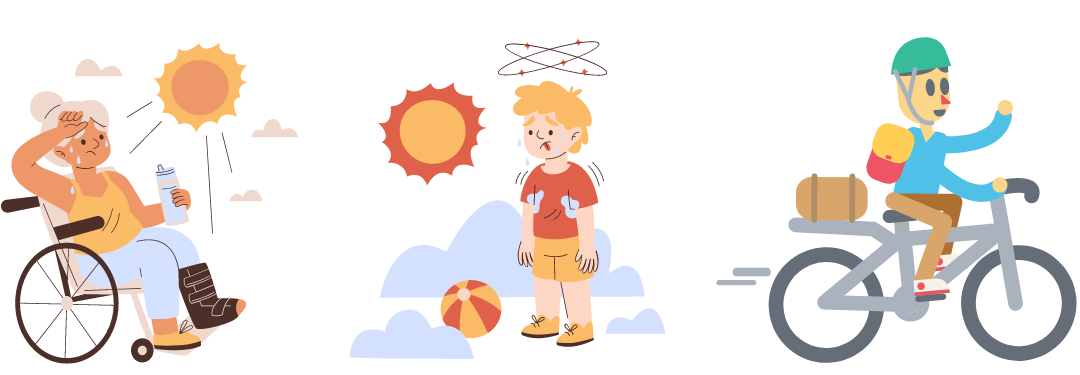

- Older adults

Older people are more susceptible to heat-related illness due to age-related physiological changes, such as reduced sweating and poor circulation, which impair the body’s ability to regulate temperature. They are also more likely to live alone, be socially isolated, or have underlying health conditions such as heart disease or high blood pressure that worsen in extreme heat.

- Children

Children, especially infants and toddlers, have smaller body sizes and a higher metabolic rate, which makes them heat up faster than adults. They also depend on caregivers to keep them safe and hydrated — and may not recognise or communicate early signs of heat stress.

- Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women

Pregnant women are at increased risk, as heat can be linked to preterm birth, low birth weight, miscarriages, and stillbirths. Breastfeeding women are also at risk of dehydration and need more fluids to maintain their own health and support lactation.

- People with Chronic Illnesses

Individuals with chronic health conditions — such as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and kidney disease — are especially vulnerable:

-

Diabetes can impair sweating and thermoregulation.

-

Kidney disease affects fluid balance and increases the risk of dehydration.

-

Heart and lung conditions are worsened by heat, increasing strain on vital organs.

-

Medications like diuretics or antihypertensives may also dehydrate the body or impair heat regulation.

People with neurological conditions like dementia or Parkinson’s may not perceive the heat or know how to respond, putting them in danger without realising it.

-

- Outdoor and Manual Workers

People working outdoors — including farmers, construction workers, delivery riders, and street vendors — are often exposed to high heat for long hours, with limited access to shade, water, or rest. Physical exertion under these conditions sharply increases the risk of heat exhaustion and heat stroke.

"Outdoor workers are extremely exposed during periods of extreme heat. Many of them spend long hours in direct sunlight, doing physically demanding work, often without access to adequate shade, water, or rest. That’s why any heat response must consider the realities faced by outdoor labourers and include specific, context-appropriate strategies to protect them." - Dr. Aina Barceló, Climate Advisor, Climate Advisor, Doctors Without Borders- Displaced People and Those in Low-Income Settings

People living in overcrowded shelters, refugee camps, or informal settlements often lack access to fans, cooling systems, clean water, or healthcare — making it harder to prevent or treat heat-related illnesses. Women and children in these settings may also face additional barriers to protection, care, or mobility.

Who is most at risk?

Extreme heat doesn’t affect everyone equally. Some people face significantly higher risks of heat-related illness and death — not only because of how their bodies respond to heat, but also due to social, environmental, or occupational factors that limit their ability to cope or access relief. These groups are especially vulnerable during heatwaves, which are prolonged periods of abnormally high temperatures lasting at least three days.

Protecting vulnerable populations during heat waves requires coordinated action. Public health agencies, healthcare providers, community organisations, employers, and individuals must work together to ensure that early warnings reach at-risk groups, resources are accessible, and heat adaptation strategies are locally tailored and inclusive.

“Heat increases the inequalities we already see — and demands a response that puts the most vulnerable at the centre.”Dr. Aina Barceló, Climate Advisor

- Stay Hydrated

-

Drink plenty of water throughout the day, even if you don't feel thirsty. Aim to consume at least 8 to 10 glasses of water daily, and more if you're engaging in physical activity or sweating heavily. And always have your water bottle with you when you are going out.

-

Avoid alcoholic beverages, caffeinated drinks, and sugary beverages, as they can increase dehydration. Choose water, electrolyte-rich sports drinks, or coconut water to replenish lost fluids and electrolytes.

-

Monitor your urine colour: Pale yellow urine indicates adequate hydration, while darker urine may signal dehydration. If your urine is dark, increase your fluid intake.

-

- Stay Cool

.png)

-

Seek out cool environments, such as buildings or community centres with good ventilation or air circulation, especially during the hottest parts of the day.

-

Use fans to lower indoor temperatures and promote air circulation. Take cool showers or baths or use damp towels to cool your skin.

-

Close blinds, curtains, or shades during the day to block out direct sunlight and keep indoor spaces cooler. Consider using reflective window coatings or insulated curtains to reduce heat gain.

-

- Dress Appropriately

.png)

-

Wear lightweight, loose-fitting clothing made from breathable fabrics such as cotton or linen. Light-coloured clothing reflects sunlight and helps keep your body cool.

-

Choose moisture-wicking clothing designed for outdoor activities, which helps to draw sweat away from your skin and promote evaporation, keeping you cooler and more comfortable.

-

Protect your head and face with a wide-brimmed hat or cap to shade your face from direct sunlight. Sunglasses with UV protection can also help protect your eyes from harmful UV rays.

-

- Limit Outdoor Activities

_0.png)

-

Minimize outdoor activities, especially strenuous exercise and physical labour, during the hottest parts of the day, typically between 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. If you must be outdoors, try to schedule activities for early morning or late evening when temperatures are cooler.

-

Take frequent breaks in shaded or cool areas to rest and cool down. Listen to your body and pace yourself to avoid overheating and exhaustion.

-

Use sunscreen with a high Sun Protection Factor (SPF) and reapply regularly, especially if you'll be spending extended periods outdoors. Sunburn can increase your body's temperature and increase the risk of heat-related illness.

-

If you notice a significant deterioration in your health during a heat wave, seek medical help immediately in the closest healthcare facility from you.

-

- Emergency preparedness

Prepare an Emergency Kit. Assemble an emergency kit with essential supplies to help you cope with heat waves and potential power outages. Your emergency kit should include:

-

Ample water: Store at least one gallon of water per person per day for drinking and hygiene needs. Consider storing additional water for pets.

-

Non-perishable food: Stock up on nutritious, easy-to-prepare foods that require little to no cooking, such as canned goods, granola bars, dried fruits, and nuts.

-

First aid supplies: Include items such as bandages, antiseptic wipes, sunscreen, insect repellent, and any necessary medications like individual medication for people with chronic diseases who take daily medications as they have a greater risk of complications and death during heat waves.

-

Portable fans or battery-operated fans: Use fans to improve air circulation and help cool indoor spaces during power outages.

-

Flashlights or battery-powered lanterns: Ensure you have adequate lighting in case of power failures or nighttime emergencies.

-

Personal hygiene items: Pack toiletries, hygiene products, and sanitation supplies to maintain cleanliness and comfort during prolonged periods without power or running water.

-

Emergency contacts: Keep a list of important phone numbers, including local emergency services, healthcare providers, and utility companies, in your emergency kit.

By being prepared and proactive, you can minimize the risks associated with heat waves and ensure the safety and well-being of yourself and your loved ones during extreme heat events.

-

Tips for staying safe during heat waves

By following these tips, you can help protect yourself and others from the adverse effects of heat waves, and you can stay safe and comfortable during periods of extreme heat.

The strain on health systems during extreme heat

Extreme heat events, particularly heat waves, put a significant strain on healthcare systems around the world — but the impact is most severe in low-resource or crisis-affected settings where Doctors Without Borders operates.

In these areas, healthcare infrastructure is often already stretched thin by conflict, displacement, outbreaks, or chronic underfunding. When a heatwave hits, the pressure intensifies.

Key Challenges Include:

-

A surge in patients suffering from dehydration, heat exhaustion, and heatstroke, all requiring urgent care — often in clinics already operating at or beyond full capacity.

-

Critical water shortages, which compromise everything from hydration to hygiene and infection control. Water is also essential for cooling systems and the preparation of oral and IV rehydration solutions.

-

Equipment failures, as extreme temperatures cause generators, fans, oxygen concentrators, and refrigeration systems (for vaccines or medicines) to malfunction or shut down.

-

Power outages, which can interrupt patient care, impact communications, and jeopardise the cold chain for life-saving drugs.

-

Travel-related fatalities, where people collapse or die before reaching the nearest health facility, especially in rural or conflict-affected areas.

In South Sudan, our hospital tents reached over 50°C. The heat caused oxygen systems to fail — placing already critical patients in even greater danger.

At the same time, health workers themselves are affected — often working long hours in suffocating conditions, wearing PPE, and dealing with rising caseloads under dangerous heat stress.

Why standard heat responses don’t always work

In places like Europe or North America, common heat adaptation strategies include access to air conditioning, public cooling centres, robust healthcare networks, and early warning systems. But these approaches don’t always work in contexts where we work, for various reasons such as:

-

Communities may lack access to electricity or clean water

-

People live in temporary shelters or overcrowded camps

-

Health systems face resource shortages and supply chain disruptions

-

Underlying issues like malnutrition, conflict, or chronic disease worsen the impact of heat

“The solutions that work in Europe or North America won’t apply in the settings we operate. In many of the places where Doctors Without Borders operates — whether it's in conflict zones, refugee camps, or areas with limited infrastructure — people don’t have access to basic things like clean water, electricity, or solid shelter. So telling people to 'stay indoors with air conditioning' or 'go to a cooling centre' simply isn’t realistic. The communities we serve face multiple, overlapping challenges — including displacement, poverty, and disease — and any strategy to address extreme heat needs to be tailored to these complex realities.Dr. Aina Barceló, Climate Advisor

This is why context matters. A heat wave in a city with functioning infrastructure is vastly different from one in a refugee camp with no running water.

Tailoring solutions through operational research

At Doctors Without Borders, we are investing in operational research to design practical, locally relevant strategies for coping with extreme heat. This includes:

-

Studying how heat affects displaced populations, patients with chronic illnesses, and healthcare delivery

-

Identifying low-cost, low-tech solutions for cooling shelters, protecting medications, and safeguarding staff and patients

-

Developing early warning and response systems that reflect real-world constraints in crisis zones

Operational research helps us understand what works — and what doesn’t — in the real-world settings where people face the greatest risks.

What Doctors Without Borders is doing to prepare for a hotter world?

Doctors Without Borders is adapting its operations to the new realities of a warming planet, recognising that extreme heat is not an isolated threat, but part of a wider pattern of climate-linked emergencies, including floods, droughts, and wildfires.

Our efforts include:

-

Delivering frontline medical care during heat waves and environmental emergencies

-

Supporting clinics and hospitals under pressure, including with mobile teams, supplies, and infrastructure

-

Promoting public health messaging on heat preparedness and hydration in vulnerable communities

-

Integrating climate risk into emergency response plans

-

Advocating for stronger climate action and equity, especially for those who are least responsible for the crisis.

The people most affected by extreme heat and disasters are those with the fewest resources to cope. We’re there when others can’t be. Stand with us.